An ancestral journey

IN 1807 THE U.S. PASSED A LAW prohibiting the importation of human beings with the intent to enslave them. Acting on a bet 53 years later, a wealthy Alabama businessman named Timothy Meaher tried to import captives from Whydah, Dahomey (present-day Benin). He hired Captain William Foster to pull off the illicit deed. On July 9, 1860, the two-masted schooner Clotilda sailed into Mobile Bay in Alabama after a three-month Atlantic crossing with 110 men, women, and children in its hold. Once the captives disembarked, Foster sailed the Clotilda up the Mobile River and set it on fire in a futile attempt to destroy the vessel and avoid prosecution. Instead, the Clotilda sank into the river’s murky waters.

This horrendous crime left an extraordinary artifact that inspired the story of my experience as a diver and underwater archaeology advocate. It is a story about ancestral memory, connectivity, resistance, and the resilience of the human spirit. It is about our collective history across the African diaspora.

I am affiliated with an organization called Diving with a Purpose (DWP), which is a global partner of the Slave Wrecks Project, a Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture program. One of DWP’s missions is documenting and preserving the stories of Transatlantic Slave Trade ships. More than 12,000 ships participated in the trade. Many vessels completed their voyages, but an estimated 1,000 vessels met their fates in a fatal wrecking event. We know very little about any of these tremendously impactful shipwrecks. I am humbled to have participated in the archaeological survey and documentation of five known slave shipwrecks: the Guerrero in John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park in Key Largo, Florida; the São José Paquete de Africa off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa; the Fredericus Quantus and Christianus Quintus in Cahuita National Park, Costa Rica, and the Clotilda. Diving on each shipwreck brought about an intense emotional response, none more so than the Clotilda.

Sadiki descends the work barge ladder

for the first dive on the Clotilda wreck site.

Incredibly, the Clotilda tragedy’s survivors established a community north of Mobile called Africatown, where their descendants still live. I began working on the Clotilda project in 2018, when another shipwreck in the Mobile River was misidentified. The project has national and international importance, particularly to the descendant community in Africatown. My first dive on the Clotilda was during a May 2022 field mission. I was working with SEARCH Inc. as part of the Alabama Historical Commission’s efforts to learn more about the shipwreck and determine, with the descendant community, the best approach to preserving this national treasure.

At times there is a stiff current flowing over the restricted wreck site, but on the morning of our first dive, the river was relatively calm. The Mobile River is mostly brackish and murky. Visibility was near zero, which only added to the site’s hazards: snakes, gators, and sharp spikes protruding from the wreck. I knew that I would have to rely heavily on touch to navigate. There is an archaeological process for evaluating artifacts for critical information about the wrecking event, the ship, and the vast historical information concerning the people who interacted with the artifact. However, there is another dimension to inferring information from artifacts, particularly slave shipwrecks.

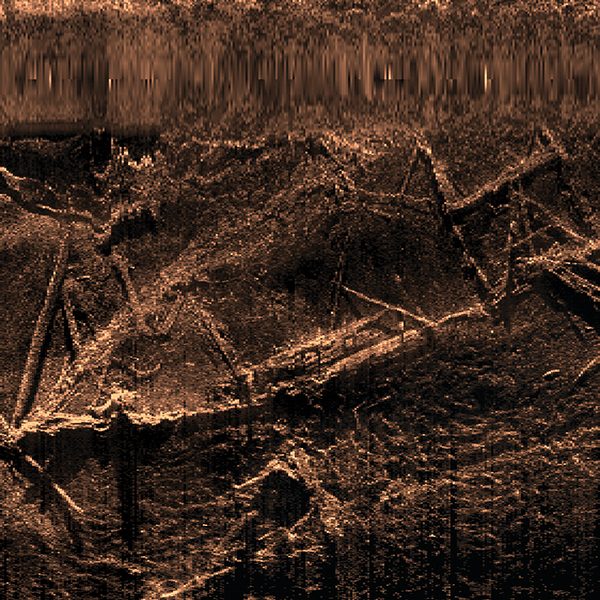

The Clotilda is largely intact as an artifact. Sonar images show about 50 percent of the vessel’s hull. The hold, a 23 by 18-foot space where the 110 captives were imprisoned, is clearly visible and only missing the deck and a portion of the hull. No other slave shipwreck in the historical record has such an accessible remaining structure that captive human beings touched as they experienced unconscionable horrors. Our emotional and physical domains are very much connected, so I expected encountering the threshold to evoke powerful reactions. With my many travels to Africa, years of studying African history, and associated life experiences, I realized that I had to prepare for this dive beyond conventional scientific diving protocols.

I anticipated intense feelings and memories to catapult me into an emotional state I had never previously experienced. Given the intensity of my dive journey to connect with the past, I had to prepare my mind, body, and spirit. My dear friend Sabrina Johnson helped compose an ancestral prayer that I recited before my first Clotilda dive, which helped calm me.

I entered the water, did a short surface swim with my dive buddy over to the shipwreck, and descended onto its bow. The visibility of only an inch or two disrupted my anticipated first visual, so I had to rely on touch. I tried to feel the voices of the 110 victims who endured so much suffering, terror, pain, and misery. As I worked my way down the starboard side, I searched for the forward bulkhead that indicated the ship’s hold. Once I felt it, I experienced an immediate sensation that is difficult to describe. I paused, knowing I was only inches away from a space like no other in the world.

A sonar image of the Clotilda in the Mobile River shows the ship’s intact hull with the visible forward bulkhead, aft of which (in the center) is the cargo hold where 110 Africans endured the horrific three-month journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

With a few fin kicks, I went up and over the gunwale into the hold. I began to explore the hold, the inner hull, the short posts supporting the lost flooring, and the thick sediment almost filling the hold’s lower portion. While I now occupied the space, it also occupied me, my thoughts holding these ancestors deep in my heart and soul. As I returned to the surface that day, I felt overwhelmed but with a heightened sense of purpose. I hope this article helps lift up the stories of the many souls that crossed oceans in ships like the Clotilda so that they are never forgotten. Such stories bring the horrific deeds of our past to life so we can honor those lost as we walk a more humane pathway into the future.

Confirming Clotilda’s location has brought the Africatown community a sense of peace with the knowledge that the artifact that forcibly brought their direct ancestors to this country still exists and will not languish as a historical footnote. The descendant community is at the center of this incredible story. The slave shipwreck can inform and transform us all in powerful ways if we know how to listen with our hands and hearts, removing the separation between the tangible and intangible. My dive experiences, particularly on the Clotilda, have given me deeper insight and meaning for this work on slave shipwrecks and enriched and strengthened my connection to my ancestors. Why do I do this work? I have no other choice. AD

Explore More

Watch these videos to learn more about Diving with a Purpose and the discovery of the Clotilda.

© Alert Diver — Q3 2022