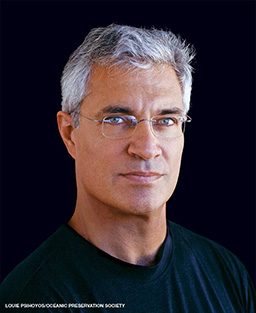

In the film Racing Extinction, Michael Novacek, Ph.D., curator of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, observes, “In 100 years or so we could lose up to 50 percent of the species on Earth.” He says it casually, as if it’s something of which people in his line of work are constantly aware. But to director Louie Psihoyos, who also directed the Academy Award-winning documentary The Cove, it was a shocking and profoundly disturbing statement.

“I remember thinking at the time that this is the biggest story in the world,” Psihoyos said. “It’s like we are all living in the age of dinosaurs, but we can do something about it.” Doing something about it is precisely the premise of this new film.

Earth has undergone five major extinction events, the most recent being the Cretaceous-Paleogene event 66 million years ago in which most scientists believe a large asteroid hit the planet, causing cataclysmic environmental disruptions that ended the age of dinosaurs. The period in which we now live is the Holocene Epoch, informally called the Anthropocene, the time of humans, and under our stewardship the limits of Earth’s ability to support life are being tested. The sixth major extinction event is looming. Psihoyos contends that we are either too late and are therefore doomed or that we might be at the beginning of a movement that could save mankind — it could go either way at this point.

The film argues that the planet’s ecosystems are in grave danger from two major threats: the international wildlife trade that victimizes rare creatures for bogus medicinal cures, trophies and status symbols, and our culture of carbon emission and ocean acidification that is incompatible with the continued survival of many of the species alive today.

“Our motto used to be ‘We’re not trying to save the whole planet, just 70 percent of it,'” Psihoyos said, referencing the oceans and the nonprofit Oceanic Preservation Society he founded in 2005. “But now I think with the new film, we’re trying to take care of the other 30 percent.” Racing Extinction‘s team of activists used state-of-the-art investigative techniques to infiltrate dangerous black markets in wildlife exploitation. The team included two highly respected ocean-conservation photographers who used buttonhole cameras and other stealth photo techniques in their travels throughout Asia.

Shawn Heinrichs gained significant credibility as a conservation photographer with his compelling video footage of shark finning in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. While so many people in China were content to eat shark-fin soup, not knowing the true cost to the species (and the global marine ecosystem), Heinrichs filmed the agony of sharks dumped like trash on the coral reef, unable to swim to pass water over their gills. WildAid used the footage in a media campaign featuring basketball player Yao Ming, then center for the Houston Rockets and one of the most famous Chinese people on the planet. The campaign was hugely successful, changing the minds of millions of potential consumers of shark-fin soup, particularly among the younger generations in China and Hong Kong.

Paul Hilton (see Shooter, Alert Diver, Summer 2014) has been influential in exposing the harvest of both shark fins and manta-ray gill rakers, and his work on whale-shark finning was essential in shaping the outcry over the practice. Along with other important players, Heinrichs and Hilton worked to get manta rays protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), a multinational treaty to conserve at-risk species, and to convince the Indonesian government to declare that entire nation a manta ray sanctuary.

This was an environmental dream team who put themselves at great personal risk to tell the story of these devastatingly unsustainable fisheries. When you consider that more than 800 environmental activists have been killed in the past decade for working to tell stories like this one, you realize this was not a casual mission.

Beyond the value of presenting staggering numbers with which the general public might not be familiar (for example, sharks have survived at least four global mass extinctions but have been reduced by 90 percent in a single human generation, with a current death rate of 250,000 sharks per day), the strength of Racing Extinction is its earnest reminder of what is now common knowledge presented with all the compelling visuals of world-class documentary filmmaking.

We know poaching is devastating wildlife. We know climate change is a problem. We know fossil fuels contribute to the acidification of the ocean, with a third to half of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the atmosphere being absorbed into that massive carbon sink that is the ocean, increasing its acidity and making it uninhabitable for some marine life. We know all this, and in Racing Extinction we see it.

Some of the ideas proposed in the film may come as a surprise. “It would be better to drive a Hummer and be a vegan than to eat beef and ride a bike everywhere,” Psihoyos suggests when discussing a path to sustainability and a minimized carbon footprint. Not only are huge portions of the earth and considerable global resources dedicated to feeding and transporting livestock, but cattle emit methane as a byproduct of metabolizing what they eat. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports that methane is at least 86 times more potent than CO2 in its ability to change the environment over a 20-year period.

The point is presented in a logical and visually powerful fashion. Reading that raising livestock generates more greenhouse gases than all the transportation factors on earth just doesn’t have the same impact as seeing the methane collected in a container on the back of a cow in just two hours. That’s what Racing Extinction does so well — it presents things we need to know in a visually compelling fashion, in the hope that we might consider changing behaviors for the greater good.

When you see Racing Extinction in the theaters in September or watch it on the Discovery Channel later this fall, it is worth waiting for the credits to roll at the end to see the names of the influential and talented people who contributed their time and wisdom to this project. When I see Jane Goodall appear on camera near the end of the film and say, “As we face more and more animal extinctions, we need more and more indomitable spirits. The small choices we make every day can lead to the kind of world we all want for the future,” I am convinced.

As Psihoyos observed regarding his hope for action based on our coverage of Racing Extinction in Alert Diver: “Let’s hope we can motivate the dive community, for they truly have the most to lose.”

Explore More

Chef Gordon Ramsay discovers the horrific acts involved in gathering shark fins and urges restaurants to stop serving shark-fin soup. (Warning: The video contains strong language and graphic content.)

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2015