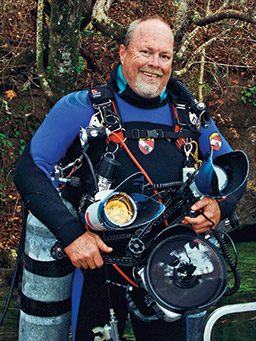

In July 2010, the diving industry lost one of its most beloved and talented photographers when Wes Skiles died on a seemingly routine dive off Boynton Beach, Fla. In an interview with Wes’ widow, Terri, “Shooter” takes a look back at the man behind the legend.

Lance Milbrand and I pushed the massive IMAX camera 300 yards through the darkness of Yucatan’s Dos Ojos cave. After swimming for 15 minutes or so, we began to see a brilliant light at the end of the long, dark tunnel. A few minutes later we emerged from the passage into a spectacularly lit crystal cathedral over 100 feet in diameter. The sight of such beauty took my breath away.

“What took y’all so long?” Wes Skiles asked jokingly. I couldn’t respond. Wes was the only one in the cave with underwater transmit capability. The rest of us could only listen. That was appropriate since Wes was director of underwater cinematography for this MacGillivray Freeman Films IMAX feature, Journey Into Amazing Caves. I didn’t need to respond. My job was to do exactly what Wes directed. That was also appropriate. What Wes was doing to illuminate and capture the beauty of this underwater cave demonstrated genius that left me humbled and in awe.

Under Wes’ direction, his team of cave divers had drilled down through 45 feet of solid rock so that light cables could be pushed through narrow holes into the Dos Ojos cave. Then Wes had positioned a dozen huge movie lights on stands throughout the 100-foot diameter subterranean room. Once the generators were switched on, the room was flooded by more than 20,000 watts of light revealing crystalline structures so beautiful and so delicate that it literally brought tears to my eyes.

“OK, let me have a look here,” Wes said as he took the camera from me and positioned it high up near the chandelier-like ceiling for the next scene. “There, I think that’s the shot,” he said passing the camera back. I gave him an OK sign then looked up at the fragile crystal-like structures hanging from the ceiling inches from where Wes wanted the camera. “Oh please don’t let me screw up and break something with all these guys watching,” I thought. Then as Wes called “action,” Dr. Hazel Barton and her buddy began swimming slowly through the room. As they moved, Wes called for various movie lights to be switched on and off, making the scene look as if the cave was being illuminated by Dr. Barton’s impossibly bright hand light. The choreography was sheer brilliance.

After the 3-minute IMAX film load was exhausted, Lance and I left the cathedral-like room and began our long swim out of the cave to reload the camera. As we swam, we could hear Wes’ Southern drawl regaling his crew with jokes and stories as the team repositioned the lights for the next sequence. To say his crew idolized Wes is perhaps not strong enough. I think they loved him.

Swimming down the long tunnel, I would occasionally look back at the brilliant blue light radiating from the end of the tunnel. Sometimes I could see Wes hovering against the light silhouetted in radiance as he directed his team.

I will never again hear or use the word “cave” without thinking of Wes Skiles.

— Howard Hall, September 2010

The way Howard Hall describes friend and colleague Wes Skiles is fairly typical of those who knew him well. It is a mixture of deep respect, passionate friendship and a heavy dose of disbelief that he is now gone. A man who defied the odds by going deeper and farther than most who’d come before him, all the while delivering incredibly creative and technologically stunning still and video images. Tragically, Wes died at the age of 52 during a relatively routine dive in only 70 feet of water off Boynton Beach, Fla.

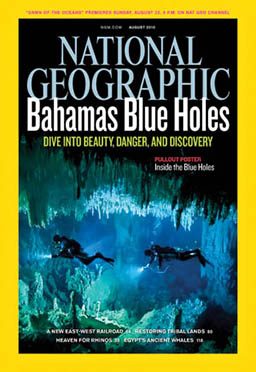

It was July 21, 2010. Wes was working with a crew photographing bull sharks. Just the day before, he’d been down in the Florida Keys to do some pick-up shots for a National Geographic television special he’d been contracted to shoot, ironically titled Speed Kills. Even more ironic, the day after Wes died, many of us received in the mail our August issue of National Geographic magazine; Wes had the cover story, including incredible photographs depicting the caves and blue holes of the Bahamas.

Traditionally our “Shooter” series involves an interview with the photographers, hearing first-hand about their inspirations and accomplishments. To my great regret, I’ll never have that conversation with Wes. His wife, Terri Skiles, very graciously agreed to speak for Wes and share in his stead his brilliant still photographs with us.

SF// Thanks for sharing your memories of Wes. I guess the best place to begin is the start of your life together. How did you meet Wes?

TS// We met in 1979 in Jacksonville, Fla. I’d just graduated from Florida State University and my parents were transferred to the naval base there. I got a part-time job in a camera store while looking for a more permanent job and met Wes when he came in to pay off a camera he’d left on layaway. He flirted a little and asked me out on a date right away, but at first I said no, thinking him far too full of himself. But then I got to know him and saw beyond the bluster. We had that first date, and I fell in love immediately. We were married in 1981, and we now have a son, Nathan, 23, and a daughter, Tessa, who is 17.

In those very early years we ran the Branford Dive Shop, north of Gainesville, and of course, we continued to dive and explore all the freshwater springs and cave systems around there.

SF// I know from guys like Spencer Slate, who also lived in Jacksonville during those years, that Wes was already a dive prodigy. In fact, Slate tells the story of his first meeting when Wes was a kid of 17; Wes was already the guy they called on to retrieve the bodies of divers who died in the area’s deep cave systems. How did he get so accomplished so young?

TS// First of all, Wes had been around diving the caves and springs for some time. He got certified when he was just 13, and he had a neighbor, Kent Markham, who built underwater scooters. Wes and his brother, Jim, had a blast as kids testing those scooters in the nearby springs, but I think what transformed him was those who mentored him, especially Sheck Exley. (Editor’s note: Sheck Exley literally wrote the book on cave diving, authoring Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival and setting the then world record in 1989 for deep cave penetration at 10,444 feet. He was also a multiple world-record holder in deep diving on both air and mixed gases. He died April 6, 1994, in an attempt to break his own deep dive record and exceed 1,000 feet.) Sheck brought Wes to the heavy-duty part of underwater cave exploration … surveying cave passages and creating maps of caves no one had ever seen before.

SF// So how did he get into photography?

TS// Both he and Jim were into photography from a very early age. They were surfers and shot 8mm movies of each other and created films of themselves. Also, Wes’ first camera was a Brownie that his grandfather had given him, so his first images were with that sophisticated camera! Wes had the perfect eye for photographic compositions, in my humble opinion. His passion toward photography was always present. He also had an intuitive sense of the science. He was self-taught, but he really understood apertures and shutter speeds and how to extract the most out of a frame of film. While he first saw photography as a creative pursuit, he soon found it had business applications, too. Not only could he document where a particular underwater cave passage went, but he could demonstrate the sheer size of these systems. They were much bigger than the scientists believed at the time, and his images could therefore illustrate the tremendous amount of water contained in these underground cave systems.

Wes started Karst Environmental Services with partner Pete Butt to help landowners define the flow path to their waters. Before long, he saw a way to bring his creative eye to photography as well and started a companion business, Karst Productions, for the stills and videos he loved to take.

SF// Wes seemed to be equally adept at still photography and video. That’s a tough transition to make. How did Wes morph into cinematography from stills?

TS// I don’t know that it really mattered much to Wes whether he was shooting stills or video. He just loved the places he was going, the adventure and being the guy who came home with the shot. By 2002 he was shooting high-definition video for a series of four hour-long DVDs called “Water’s Journey” for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the different water management districts as well as Florida’s Department of Education and PBS. Earlier he was shooting 16mm film for National Geographic documenting Bill Stone’s cave expeditions, Shark Week footage for the Discovery Channel and The New Explorers with Bill Kurtis back in the 1980s and 1990s, and of course one of his fondest memories was working with Howard Hall on the IMAX film Journey Into Amazing Caves. His work on the theatrical release The Cave, as well as the most recent work on Discovery’s Time Warp and NOVA’s Extreme Cave Diving, was HD video.

Lighting underwater caves systems became a specialty for Wes, and he was probably the best in the world at it. He actually designed some of the very early lights used in cave videos.

SF// I think we all know Wes best as the master at cave exploration and documentary, but he was a very eclectic shooter, with a wide range of coverage.

TS// Yes, absolutely! Wes was often on expeditions, whether to the Yucatan for some big cenote project, or off to Fiji, Africa or the Red Sea. Actually, several of these expeditions went on for months at a time. I remember him leaving from New Zealand on an icebreaker to travel to Antarctica to photograph and film a giant mass of ice that had broken off the continent. This was back in the year 2000 and probably one of the early stories about global warming.

Sometimes he traveled with his crew, and occasionally I went along to help. We had a shoot in British Columbia, and I was able to go along and assist for three weeks, and it was one of the best times of my life! Later, when the kids got older, we felt they could join an expedition here and there and “see Dad work.” I remember very special trips to the Bahamas and the Yucatan like that. Eventually, Nathan worked with his dad a lot, and in fact, in the cover shot on the August National Geographic, Nathan is one of the divers. That made Wes very proud.

SF// Did that bother you, him being gone so long and doing such perilous jobs?

TS// Not really. I was a Navy brat, and my parents taught me well about time spent away from home. I most often stayed home with the kids, but sometimes we would go on expeditions together.

As for the hazard, I really never worried much. I knew Wes had the skills and experience to be safe, even though others might have considered what he was doing quite extreme. Actually, I worried a lot more about him when he went horseback riding or rode his motorcycle. Diving was something he knew, and he always felt he was in control of the variables.

You know, for Wes I think it was all about the love of adventure. He had this childlike enthusiasm to explore and share what he found with others. He wanted people to understand what he knew to be true by experience and observation. Take the Florida aquifer for example, he knew it was being poisoned, but he wasn’t against the farmers and their fertilizers, and he wasn’t for all the causes of the environmentalists, either. He was never against any one group when it came to figuring out issues or potential solutions pertaining to underwater pollution. Rather, he tried to bring together those who seemed to be opponents to talk and work things out. Whether he was ultimately successful or not, this was always his clearly defined approach. Without his films demonstrating how all was interconnected, neither party could understand or relate to the bigger issues.

SF// Wes was a master of diving technology, he had to be for the places he went and the length of time he stayed underwater to perform his craft. How did he develop his expertise?

TS// The fact that Wes died while using a rebreather will likely be a source of speculation for some time, but even today I don’t know exactly what caused Wes’ death. I do know the general details of his 70-foot dive, but he was alone when he died, on his way back to the boat to service his camera. As for his experience in technical dive matters, he’d used rebreathers for a very long time in his career as a filmmaker. He was with Bill Stone in 1987 on the Wakulla Springs project when the Cis-Lunar rebreather was used for the first time, and he logged plenty of time on that. He probably had more hours on the later iteration, the Cis-Lunar MK5, than any other particular rebreather. In 2004 he was hired as the chief underwater cinematographer for an action/horror movie called The Cave, and he spent many weeks shooting on underwater sets in Romania and in the caves of the Yucatan. There he became very familiar with the Megalodon rebreather. Wes was definitely very savvy about technical dive gear and techniques.

I can’t postulate why he died, but I know he loved to live. He loved his friends, and they gathered around him like moths to a flame. He loved fireworks and bonfires and to laugh and to throw a great party. He loved to explore and to dive and to shoot photos and movies. He loved his family. And I loved living life through his adventures.

Wes Skiles was the best there ever was at documenting the rare and wonderful underwater cave and cavern systems of the world. He was a technological innovator and a brilliantly creative image-maker. He was a passionate advocate for Divers Alert Network® and one of our most high-profile inspirations for both recreational and scientific scuba diving. His friends, his family and the whole dive community mourn his loss, yet we celebrate his many significant achievements. — Stephen Frink

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2010